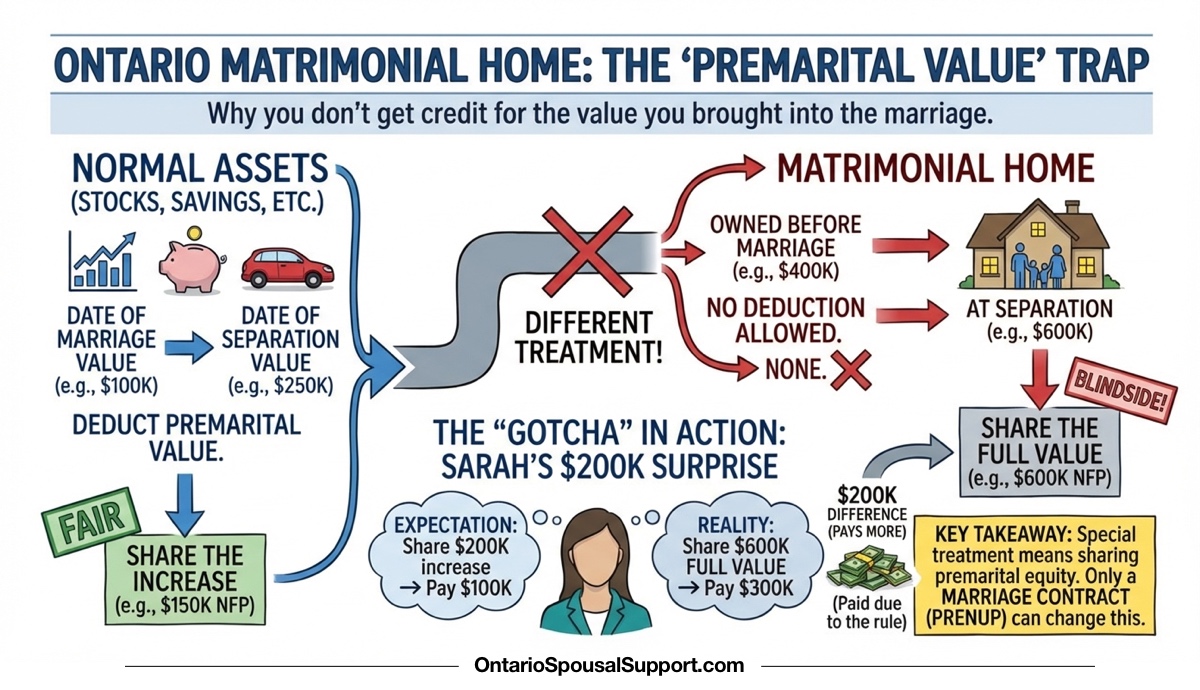

In Ontario, the matrimonial home is treated completely differently from every other asset. The premarital value you brought into the marriage? You don't get credit for it. The full value at separation gets split.

This blindsides people every single day. And it can cost you hundreds of thousands of dollars.

If you owned your home before marriage and it's still the family home when you separate, here's what you need to know: under Ontario's Family Law Act, you cannot deduct the value you brought into the marriage. Not a dollar of it.

The Matrimonial Home Rule in 30 Seconds

Normal assets: You deduct what you brought into the marriage. Only the increase during marriage gets equalized.

Matrimonial home: No deduction allowed. The FULL value at separation is included in your Net Family Property.

Why it matters: If you owned a $400,000 house before marriage that's now worth $600,000, you're not just splitting the $200,000 increase. You're effectively sharing the whole $600,000.

The only protection: A marriage contract (prenup) signed before or during the marriage.

How This Actually Works (The Math That Hurts)

Let's walk through the numbers so you can see why this matters so much.

How Normal Assets Work

For most assets, Ontario's equalization system is straightforward:

- Calculate what you owned at the date of marriage

- Calculate what you own at the date of separation

- The increase during marriage is your "Net Family Property"

- The spouse with more NFP pays half the difference to the other

So if you had $100,000 in investments when you got married and $250,000 when you separated, your NFP contribution from those investments is $150,000 (the increase). Fair enough—that growth happened during the marriage.

How the Matrimonial Home Works (Differently)

The matrimonial home gets special treatment. Bad special treatment if you're the one who owned it before marriage.

You cannot deduct the value of a matrimonial home that you owned at the date of marriage. The full value at separation is included in your NFP.

Example: The $200,000 Surprise

The situation: Sarah owned a house worth $400,000 when she got married. At separation 8 years later, it's worth $600,000. Her spouse, Michael, owned nothing at marriage.

What Sarah expects: "I'll share the $200,000 increase. So I owe Michael $100,000."

What actually happens: Sarah can't deduct her $400,000 premarital equity. Her NFP from the house is the full $600,000. Assuming no other assets or debts, she owes Michael half of $600,000 = $300,000.

The difference: Sarah pays $200,000 more than she expected because of the matrimonial home rule.

This feels deeply unfair to many people. Sarah owned that house for years. She made the mortgage payments. She maintained it. And now she's sharing value she brought into the marriage?

Yes. That's the law. The rationale is that the family home is special—it's where the family lived, and both spouses should share in its value regardless of who originally owned it.

Whether you agree with that rationale or not, it's what the Family Law Act says.

The Side-by-Side Comparison

Here's how the matrimonial home differs from every other asset:

| Factor | Regular Assets | Matrimonial Home |

|---|---|---|

| Premarital value | Deductible from NFP | NOT deductible |

| Inherited money used to purchase | Excluded from NFP | Loses exclusion |

| Gifts used to purchase | Excluded from NFP | Loses exclusion |

| Whose name on title | Matters for ownership | Doesn't affect equalization |

| Possession rights at separation | Owner controls | Both spouses have equal rights |

What Qualifies as a "Matrimonial Home"?

The definition is broader than most people think. Under the Family Law Act, a matrimonial home is:

"Every property in which a person has an interest and that is or, if the spouses have separated, was at the time of separation ordinarily occupied by the person and his or her spouse as their family residence."

Here's what that means in plain English:

It's About Use, Not Ownership

If you and your spouse lived there together as your family home, it's a matrimonial home. Doesn't matter whose name is on the title. Doesn't matter who paid for it. Doesn't matter who found it or negotiated the purchase.

If it was your family residence at separation = matrimonial home.

You Can Have More Than One

Have a cottage you use regularly as a family? That could be a second matrimonial home. The law says "every property" that meets the definition—not just one.

This means if you owned a cottage before marriage and kept using it as a family property, both the main house AND the cottage could be matrimonial homes. Neither would get a premarital deduction.

Ontario Properties Only

The matrimonial home rules only apply to properties in Ontario. If you own a vacation property in Florida or BC, it's not a matrimonial home under Ontario law (though it's still subject to equalization as a regular asset).

The "I'll Put It In My Name Only" Trap

Some people think they can protect their premarital home by keeping it in their name only. This doesn't work.

Title affects who legally owns the property. It doesn't affect equalization.

Even if the house is 100% in your name:

- The full value still goes into your NFP

- You still can't deduct the premarital value

- Your spouse still has equal possession rights until the divorce is finalized

- You can't sell it without your spouse's consent while it's still the matrimonial home

Title protects you from your spouse taking ownership of the house. It doesn't protect you from sharing its value through equalization.

When Inheritances and Gifts Lose Their Protection

Normally, inheritances and gifts from third parties are excluded from equalization. You don't have to share them.

But there's a catch: if you put that money into a matrimonial home, the exclusion disappears.

Example: The Inheritance That Vanished

James inherits $150,000 from his grandmother. He uses it to pay down the mortgage on the family home.

At separation, James thinks: "That $150,000 was my inheritance—it's excluded."

Wrong. Because he put it into the matrimonial home, it lost its exclusion. That $150,000 is now part of the home's equity and will be equalized.

If James had put that inheritance into an investment account instead, it would remain excluded.

This applies whether the money was used for:

- The down payment

- Paying down the mortgage

- Renovations or improvements

- Any other contribution to the home

The lesson: think carefully before putting inherited money or gifts into your family home. Once it's in, it's shared.

The One Loophole: Selling Before Separation

There is one way the premarital value can be preserved: if you sell the home before separation and it's no longer the matrimonial home when you separate.

The matrimonial home rules only apply to a property that is the matrimonial home at the date of separation. If you sold it earlier and bought a different house, the original home's premarital value can be deducted.

Example: The Strategic Move

Lisa owned a condo worth $300,000 when she got married. Three years into the marriage, she and her husband sell it and buy a house together.

At separation, the condo is long gone. The new house is the matrimonial home.

Result: Lisa can deduct her $300,000 condo value as a date-of-marriage asset, because the condo was sold and is no longer a matrimonial home. Her premarital equity is preserved.

This isn't really a "loophole"—it's how the law is designed. The special rules protect the home the family is actually living in. Once a property is sold, it's no longer "the matrimonial home" and normal rules apply.

How to Actually Protect Yourself: Marriage Contracts

The only reliable way to protect premarital home equity is a marriage contract (prenup).

Ontario's Family Law Act allows couples to contract out of the standard property rules. You can agree that:

- The premarital value of the home won't be shared

- The home will be treated like any other asset (with premarital deduction)

- The home belongs entirely to one spouse

- Some other arrangement that works for your situation

Marriage contracts are especially common for:

- Second marriages where one spouse has a home from before

- Significant age differences where one spouse has more assets

- Situations where one spouse is bringing substantially more to the marriage

Requirements for a Valid Marriage Contract

For a marriage contract to hold up in court:

- It must be in writing and signed by both parties

- Both parties should have independent legal advice (seriously—don't skip this)

- There must be full financial disclosure

- Neither party can be under duress or undue pressure

- The terms can't be unconscionable (grossly unfair)

A DIY prenup downloaded from the internet is risky. Get a lawyer. The cost of doing it right is nothing compared to the cost of it being thrown out when you need it.

What If We're Already Married (Without a Contract)?

You can still sign a marriage contract during the marriage—it doesn't have to be before the wedding.

That said, getting your spouse to agree to give up rights they already have is harder than getting them to agree before marriage. The conversation is awkward. They might refuse. They might see it as a sign you're planning to leave.

But if protecting your premarital equity is important to you, it's worth having the conversation. A postnuptial agreement can still work.

Common Questions People Ask

"But I paid the mortgage for 5 years before we got married!"

Doesn't matter. The value at marriage date is still not deductible if it's the matrimonial home at separation.

"What if my name is the only one on the mortgage?"

Mortgage responsibility doesn't affect equalization. You might owe the bank, but you still share the equity with your spouse.

"Can I at least get credit for the payments I made before marriage?"

No. Those payments built equity that would be your premarital deduction—but the matrimonial home rule eliminates that deduction.

"What if my spouse never contributed to the mortgage?"

Doesn't matter. Equalization doesn't care who made payments. It looks at net worth, not contributions.

"This seems really unfair. Can a judge make an exception?"

The law does allow for "unequal division" in circumstances where equalization would be "unconscionable"—but that's a very high bar. "It doesn't seem fair" isn't enough. You'd need exceptional circumstances. Don't count on this.

Try the Property Division Calculator

Want to see how the matrimonial home affects your equalization payment? Our property division calculator walks you through the Net Family Property calculation—including the matrimonial home rules.

The calculator will help you understand how different assets are treated and what you might owe (or be owed) at separation.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I deduct the value of my house that I owned before marriage?

No—if it's still the matrimonial home at separation. Unlike every other asset, you cannot deduct the premarital value of a matrimonial home. The full value at separation gets included in your Net Family Property. This is the single biggest gotcha in Ontario property division.

What is a matrimonial home in Ontario?

A matrimonial home is any property that was ordinarily occupied by you and your spouse as your family residence at the time of separation. It's about use, not ownership. If you lived there together as a family, it's a matrimonial home—regardless of whose name is on the title or who paid for it.

Does putting the house in my name only protect it from equalization?

No. Title doesn't matter for equalization purposes. Whether the house is in your name only, joint names, or your spouse's name, if it's the matrimonial home, the full value at separation is included in your Net Family Property. Title only affects who technically "owns" it—not how it's divided.

What if I used an inheritance to buy or pay down the matrimonial home?

The inheritance loses its exclusion. Normally, inheritances are excluded from equalization. But if you put that money into the matrimonial home—as a down payment, to pay down the mortgage, or for renovations—the exclusion disappears. The money becomes part of the home's value and gets equalized.

Can I protect my premarital home with a prenup or marriage contract?

Yes. A marriage contract (prenup) can contract out of the matrimonial home rules. You can agree that the premarital value of the home won't be shared, or create other arrangements. This is especially common in second marriages. But the contract must be done properly—get a lawyer.

What if we sell the matrimonial home and buy a new one during the marriage?

This is one way to preserve your premarital equity. If you sell the home you owned before marriage and buy a different one, the original home is no longer the matrimonial home. You can then deduct your premarital equity as a date-of-marriage asset. The new home's value at marriage becomes your deduction baseline.